Tags

Do you have stories to share about Pancho Villa and the Avalos smelter?

This 1914 photo courtesy of the LIFE magazine photo archive on Google shows Mexican General Pancho Villa riding with his men after victory at Torreon.

From The Life and Times of Pancho Villa by Friedrich Katz, 1998, pp. 415-416, Mr. Katz discusses the dilemma Pancho Villa faced in dealing with the American owned mines and smelters in 1914, “…but the fighting in Chihuahua, as well as reduced demand for ore on international markets, had led most mining companies to curtail or abandon mining altogether in Chihuahua. Villa’s main interest was to have the large foreign companies, above all the American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO), resume work in Chihuahua. Villa had two options for achieving this. The first was to grant the mine owners every possible condition they could wish for to resume operation. The second was to threaten them with the occupation of their holdings and state operation of the mines if they did not.”

In this 1916 NY Times article, refugees had begun to flee Mexico. All ASARCO employees from the Chihuahua smelter fled to El Paso, Texas by train.

Isaac F. Marcosson wrote in his 1949 book Metal Magic: The Story of the American Smelting and Refining Company pp. 231-233, “It is a tribute to ASARCO’s staff that during the ten years of constant bloodshed and disorganization, the life of not a single Company employee was lost by violence, although hundreds were scattered over Mexico, often in isolated plants and mining units. Nor was a single property seriously impaired. This was due to the loyalty of the Mexican workers who remained on the job, and to the tact and judgment of the organization, which assumed a neutral attitude in the political strife that prevailed. During all this disordered decade, ASARCO engaged in two enterprises that required a high order of courage in view of the existing conditions and the investment required. One was the rebuilding and expansion of the Chihuahua plant; the other was the purchase of the Rosita properties.”

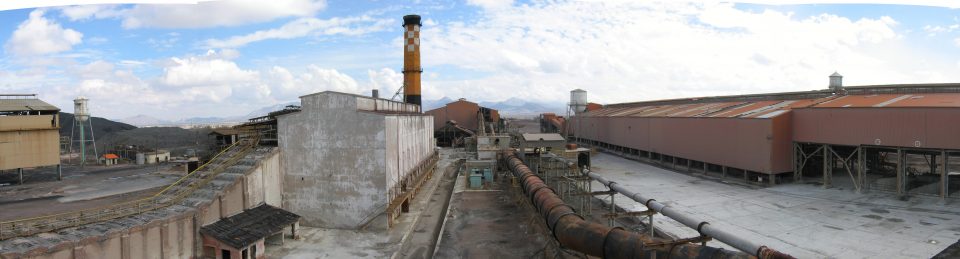

Marcosson continues, “The reconstruction of Chihuahua was carried out in circumstances that produced many and sometimes exciting episodes. Due to inadequate military protection and a threat by Villa to blow up the smelter unless a million dollars was paid for immunity, the plant was built behind a barricade of adobe-and-stone forts (one of them was called Fort Woodul), walls, and pillboxes.”

“During a brief period just previous to Obregon’s entrance into Chihuahua with Federal forces, the plant was abandoned. Villa seized it and for a short time undertook operations with the forced assistance of some of the native workers. Being short of cash, he paid the men in slices of lead bullion. It shone and looked like silver, so the bandit took it at its “face” value. The workers, however, were not deceived.”

“It was during one of Villa’s visits to the Chihuahua plant that there emerged the classic remark that went the length and breadth of Mexico. Some one asked him in Spanish if he spoke English. His reply was: “Si. ‘American Smelting’ y ‘son-of-a bitch.’ ” It was all the English he knew.”